Why Autocorrect Might Be ‘Ducking Up’ Your Sext Life

Your smartphone and its prudish bias against sexual language.

Try typing “vagina” with your iPhone. It will allow it if you get it right.

But get it wrong? “Cagina” becomes “carina,” “bagina” becomes “banging,” and so on and so forth—despite the fact that “vagina” is almost certainly used with more frequency in our day-to-day lexicon than “carina”—a ridge of cartilage in the trachea.

Autocorrect refuses to believe, or accept, that you actually meant to type “vagina” but hit the nearby “c” or “b” instead of the “v.”

Most of us have encountered the frustration that comes with an impassioned “fuck” being changed into a much less emotionally charged “duck.”

The man behind Apple’s autocorrect software says that autocorrect is trained to avoid swear words to prevent people from accidentally sending them, (maybe you were actually texting your mom about a duck!).

While that may be so, it’s evident that autocorrect’s unwillingness to recognize sex-related language is the result of software programmed under the assumption that such language is bad, unwanted, and that your use of said language, even if by mistake, would be so embarrassing that your keyboard must be programmed to avoid such an error.

Autocorrect algorithms, in particular, are praised for their ability to know our language, know our language habits, and be able to predict what it is we want to say. But when they disallow us from swearing or refuse to acknowledge that “vagina,” or “sex” might actually be what we intended to type, they are correcting our language, too.

The subtle way our technology encourages us to use certain language in place of language it views as socially unacceptable is, at best, frustrating and paternalistic. It’s censorship at its most subtle, and it’s grounded in historical social norms that dictate what is acceptable and what is obscene.

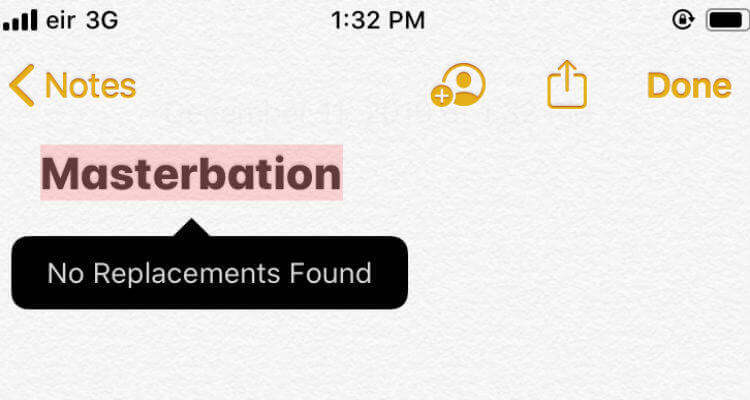

With Apple’s autocorrect, “sez” becomes “set” instead of “sex” despite its physical distance from both “z” and “x.” If you misspell “masturbation” as “masgerbation,” hitting the “g” instead of the nearby”t,” your iPhone will not offer any suggestions for the misspelled word. Instead, it will tell you “no results found,” as if the word for the act of self-pleasure isn’t even in the dictionary.

That’s exactly the problem.

Autocorrect, like its predecessor, Microsoft’s Spellcheck, are programmed with their own dictionaries. While these dictionaries appear to include words like sex, vagina, and masturbation—as these words aren’t underlined in red when they are spelled correctly—it’s clear that the dictionaries have been programmed to avoid suggesting any sex-related language, even language dealing with our sexual anatomy.

As I type this on an Apple iPad, it refuses to correct “lacia,” “lania” or “lavia” to my intended word choice of “labia.” In fact, it would rather assume that misspelling of the word “penis” as “pdnis” be corrected to “punishment.” Punishment indeed, you naughty texter.

This bias is certainly not limited to iPhone’s autocorrect software; there is no shortage of articles and how-tos about how to get Android keyboards to allow its users to swear or use other “obscene” language without hindrance.

The algorithms that automatically sort our e-mail, too, contain similar bias. If your email address or subject line contains the word “sex” or a word related to sex, you might find that you often have trouble emailing new clients, customers, or friends.

That’s because the algorithm we rely on to sort our mail into the category of either “normal” or “important” versus “junk” or “spam” often determines sex-related language to be the latter.

The fact remains that our technologies’ unwillingness to accept swears and explicit sex-related language demonstrates a built-in bias in the algorithms behind the software; a bias that often makes it feel like your grandmother wrote the code.

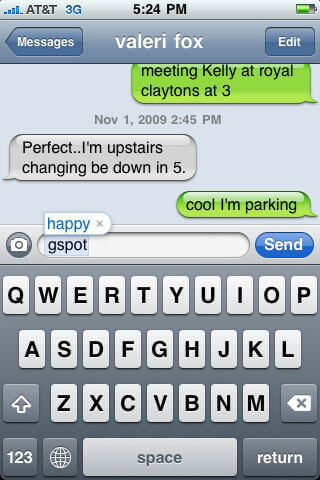

While autocorrect and its Android cousins’ insistence on “clean” language might seem like no more than an annoyance in the middle of your sexting session, the bias behind it is political in nature. It boils down to an age-old debate on what is considered acceptable public language versus what is considered obscene.

For centuries, sexuality, especially female sexuality, has been considered taboo, obscene, immoral, and in some instances, it’s been criminalized as a result.

Public speech and art began to be censored on the grounds of sexual obscenity in the mid-19th century in the United States and Britain. At the time, the legislation was controversial and very wide reaching.

In the U.S. in particular, not only was pornography censored, but according to Encyclopaedia Brittanica, so were publications giving medical advice on contraceptives and abortion.

While obscenity law does still exist in the Western world, it has loosened up significantly over time, allowing pornography industries to flourish, for instance. However, anti-sex principles have followed us into the 21st century and influence the way we interact with our tech.

Further evidence of this, for example, is Instagram’s insistence on removing posts it considers to be “sexually suggestive,” a policy that has resulted in the removal of pictures featuring period blood, pubic hair, and otherwise deviant representations of female and non-binary bodies.

When we think about the censorship of sex, or sexually-related content, we typically think of how this affects public expressions of obscenity or sexuality.

And while public expressions of obscenity and/or sexuality are indeed being actively censored on the Internet, the subtle signals the algorithms in our phones send us bring those moralizing values into some of our most private and intimate interactions.

Image sources: Chelsea Nash, dana robinson

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.