Does Having an IUD Make You a Biohacker or a Cyborg?

Pondering the T-shaped implant’s role in altering human reproductive anatomy.

Humans have been pushing the limits of our bodies for decades to achieve better sex.

We go through foreskin restoration, take pills to treat erectile dysfunction, and even dream up ways to reroute the nerves in our vaginas.

There’s an overarching term for all of this: Biohacking.

Biohacking aims to expand the range of the body’s potential by incorporating various hacks into our natural biology. These hacks range from gene editing and drug use to physical body modifications and implants. For the sake of this article, we’ll focus on the latter.

Because it’s such a diverse movement, there’s no set definition for what makes something biohacking. If we look at the intersection of sex tech and biohacking, most agree that something like turning yourself into a human vibrator “counts” as biohacking.

But when we explore further into sexual wellness and reproductive health, it becomes distinctly… less clear. Take an IUD, or an intrauterine device.

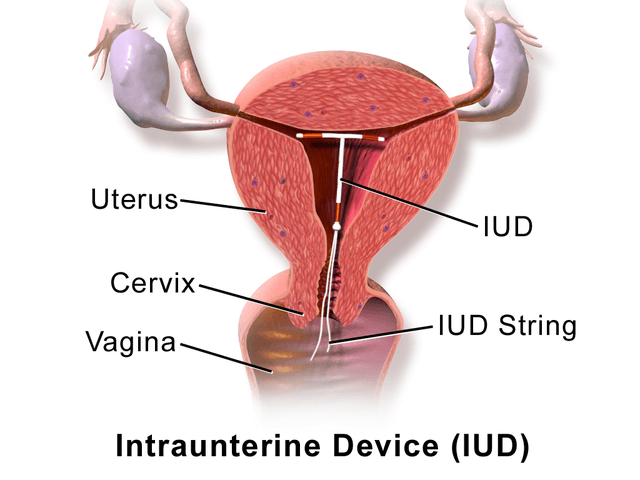

What’s an IUD?

These tiny T-shaped devices are made of plastic or copper and inserted into the uterus to prevent pregnancy. They work by changing the way sperm cells move so that these sperm cells can’t reach an egg.

Once it’s in place, an IUD is more than 99% effective against pregnancy for 3 to 12 years—without any required maintenance from the owner.

So, it’s an implanted device that alters how a biological process functions.

Does this mean that someone with an IUD is a biohacker?

Well, that depends on who you ask. To some, it’s not just about the specific device being used, but rather how that technology is being applied.

This is how Hannes Sapiens sees it. Sapiens is the managing director of Dsruptive Subdermals, a health tech company in Sweden focused on implantable microelectronics. To him, the determining factor for whether an IUD would be biohacking or a medical intervention depends on how the device is being used in relation to the intended purpose.

“Typically, there’s some kind of curiosity or exploration component to hacking. This doesn’t necessarily mean that you need to invent something completely new, but rather you took something that’s used for a certain purpose and then use it for another purpose,” he explains.

Another factor to consider is how the device is built and the type of inspections it goes through (if any). According to sexologist Carol Queen, it matters.

“[An IUD] is a human hack of our reproductive anatomy, right? But it went through the scientific process in its development… whereas, say, the person who wants to implant a vibrator under the skin really is experimenting on themselves,” says Queen, who works as a staff sexologist at Good Vibrations in San Francisco.

She adds: “Mainstream information, including science and medicine, barely delves into knowledge about sexuality—you have to specialize to get that.”

Both Sapiens’ point about purpose and Queen’s question of scientific authority is echoed by medical professionals. These considerations contribute to many other facets of implanted reproductive health. For instance, who is able to properly insert or remove a device and whether that device can be covered by insurance.

“I don’t think I’d put IUDs in the category of biohacking since my understanding is that biohacking includes some element of do-it-yourself, and IUDs are firmly part of traditional, evidence-based medicine,” says Dr. Gillian Dean, director of medical services at Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

She cites the United States as an example: “All five brands of IUDs available are FDA-approved, and there’s not really a ‘hack’ involved—people use them exactly how they’re designed to be used.”

Among people who actually have an IUD, opinions also vary.

“My IUD is not disruptive,” says Haleigh Thomas, a social worker from Wisconsin.

“It’s a mechanism to bring my future plans to fruition. It helps me create a timeline that truly is tailored to me and my ambitions, needs, opportunities.”

Barcelona-based software engineer Vanessa Yuen disagrees:

“If drinking over-glorified SlimFast counts as biohacking, then having a device in my uterus 24/7 that ‘hacks’ my body into not making babies definitely qualifies me as a biohacker.”

Does implantable birth control make you a cyborg?

But according to Dr. Dean, we could just be asking the wrong question:

A more appropriate question might be if having an IUD makes you a cyborg. I think you could make a pretty strong argument there if we define a cyborg as someone whose human physicality or abilities are enhanced by implants or other technology.

This is part of the beauty of biohacking. Because it’s such a broad subculture, people are able to self-identify and join the community as they see fit.

“Anyone who self-identifies as a biohacker is, in my view, super welcome to do so,” says Sapiens.

“No matter if you’re taking supplements, hacking your sleep, or if you’re a hardcore body mod individual, welcome. Welcome to the show.”

Regardless of if you consider an IUD a hack, it’s hard to deny the potential impact that emerging technology—and specifically biohacking—will have on reproductive health.

“[Exploring this space] makes talking about reproductive health interesting in novel ways,” says Sapiens.

Maybe we can discover some completely new benefits from these devices. Maybe we can stick sensors in there and gather statistics or maybe we can put LED lights in them. And who knows what that might lead to in terms of exploring novel dimensions of what we humans can experience.

Image source: Sarah Mirk, BruceBlaus/WikimediaCommons, Sarah Mirk