What I Learned About Humanity As a Sexbot Researcher

Audrey Pope unveils her scholarly pursuit of erotic robotics.

Everywhere I turn, it seems, I’m faced with another example of our growing fascination with the intelligent robot.

I’ve found myself stumbling upon advertisements for events like The Man Machine, an exhibition of films and events about robot technology at the EYE Film Museum in Amsterdam. There, I saw screenings of Her and Ex Machina for the first time and was introduced to Hollywood’s adaptations of the ideas I was exploring.

I also attended the Robot Love expo and convention in Eindhoven—a once in a lifetime experience—where artists and scientists came together to question whether or not love can exist between humans and machines.

These experiences, among others, have made it clear that robotics and artificial intelligence have already begun to pervade our world.

Since then, I have found myself time and time again with the opportunity to explore the presence of robots in my own life, and if nothing else, I find myself with an argument in favor of David Levy’s claim in his widely popular book, Love and Sex with Robots: the robots are coming. We had better start talking about it.

The idea

It is, of course, no question that sexuality has long been considered a marker of human modernity: the nuanced, human approach to sex being one of the finest examples of what makes us such a (self-proclaimed) advanced species.This, coupled with the human mastery of tools, can be cited as responsible for our separation from the rest of the animal kingdom. The junction between sex and technology, therefore, is undoubtedly worth considering as an examination of humanity, at large.

Sex robots, then, as the exemplar of this juncture, can be looked at not only as the holy grail of sex toys but rather as representative of something much more abstract: a reflection of what makes us human.

The opportunity to tackle this daunting theoretical question was too good for me to pass up. I wanted to take a stab at finding an answer, and I wanted to combine sex robots and critical theory to do it.

The survey

When I say it out loud, it almost seems too simple: it’s the body. The bodies of sex robots are what really makes them special.

We could—and are already beginning to—combine advanced software and sophisticated mechanics in a myriad of ways, creating devices capable of pleasuring us with nuance and individuality.

But rarely do these possibilities evoke concerns of ethical thin ice the same way robots tend to. I wanted to know why.

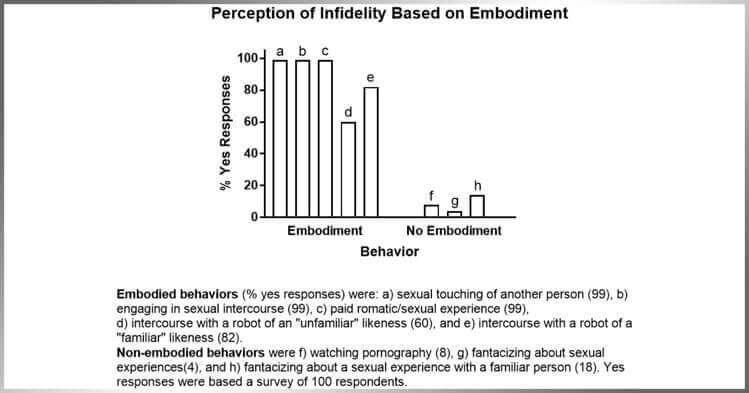

So, I set out to see how people perceived the impact of embodiment as it pertains to sex robots. I released an online survey, asking people whether or not they would consider certain behaviors to be cheating on a partner.

The behaviors ranged from those that don’t rely on embodiment at all (like watching pornography), to those that do depend on embodiment (like engaging in sexual intercourse). Among these behaviors, I included questions describing intercourse with a human robot.

The results were starkly apparent. Behaviors which relied on embodiment were much more likely to be considered cheating on a partner, illustrating the importance of embodiment in actualizing sexual behaviors.

In other words, the data show that embodiment is what makes most humans perceive sexuality as real. So, when we’re talking about sex robots, as opposed to basic sex toys or virtual sex games, their bodies, even though artificial, make them significantly more likely to be considered “real” sexual beings.

Virtual reality

One surveyed behavior illustrates this conclusion particularly well: the use of virtual reality technology for sexual fantasy. This question received the most evenly distributed results, with percentages coming in near 50/50.

One surveyed behavior illustrates this conclusion particularly well: the use of virtual reality technology for sexual fantasy. This question received the most evenly distributed results, with percentages coming in near 50/50. Virtual reality is unique because it incorporates aspects of both imaginative fantasy and realistic, embodied pleasure. The more advanced the specific piece of technology or program is, the more realistic the fantasy becomes.

It is possible, consequently, that the divide of opinions on this subject is related to differences in understanding or previous experience with VR. That is to say, if an individual has had experience with advanced and immersive VR technology, they are more likely to believe that using VR for sexual pleasure constitutes cheating on a partner.

On the other hand, if an individual does not perceive or has not experienced VR technology as capable of presenting a realistic experience, they are more likely to characterize using VR for sexual pleasure as purely imaginative.

Virtual reality thus bridges the gap between technological imagination and reality. In this way, it differs from a sex robot only in embodiment. The distribution of responses to this survey question, then, show us exactly where people draw the line, where real sexuality is distinguished.

What does it all mean, though?

Knowing that sexuality is actualized through the body helps explain why people so often think about sex robots with discomfort. Not only are we talking about bodies, we’re talking about our bodies. And this is where things get crazy.Sex robots are loaded with representational content, the idea that these machines represent much more than the summation of their mechanical parts.

For example, when we talk about the ethical concerns of consent with sex robots, we’re not really worried about violence against mechanical objects or the abuse of artificial intelligence. Instead, we’re worried about what these behaviors represent.

So while we may know that these are machines, there’s this kind of gut reaction that there needs to be boundaries for how we interact with them. This is where the deeper meanings humans associate with sex robots begin to play out.

Theorist Masahiro Mori coined the phrase “uncanny valley” to describe the discomfort humans feel when we interact with humanoid forms.

My research piggybacked off of this idea, combining Mori’s uncanny discomfort with the work of theorist Jacques Lacan, who wrote about mirror theory. Lacan argues that seeing your reflection, either in a mirror or in the similarities of another body, is crucial for understanding who you are. Looking at a humanoid robot, then, is an opportunity for humans to recognize their own humanity.

I continued drawing inspiration from other theorists, building an argument to say that the fear or discomfort we feel with robots causes us to respond in ways that emphasize our power as humans, thus queuing up all of the ethical concerns that we talk about with sex robots, in particular.

I look at Cohen’s ideas of monster theory, exploring the ways that bodies are marked as different and, therefore, both dangerous and desirable. I turn again to Lacan, building off his ideas of transitivism and our inherently aggressive responses to difference. Lastly, I turn to French philosopher Michel Foucault, who argues that humans act in service of power systems.

Each of these theorists and their ideas about human nature contribute to my argument about what sex robots can tell us about our own humanity—namely, how precarious of a label that really is.

The development and employment of sex robots is actually just an avenue for the execution of human power. The ability to create and consequently control these machines is representative of something more than the actual function of these robots.

Rather, the ability to conquer these machines is representative of the conquering of a much more abstract fear, which, pessimistically, I argue is the fear of human fragility. Recognition of the idea that the human body is a site of both fear and desire and is one that can be both imitated and controlled is a source of aggression, and I argue that the employment of robots is merely a response to this apprehension.

Image sources: Audrey Pope

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.