Sex Tech Study Guide: A Cyborg Manifesto

An overview of Donna Haraway’s feminist pivotal text.

One of the most relevant texts for the sex tech industry is Donna Haraway’s 1985 essay, “A Cyborg Manifesto.” Haraway, Distinguished Professor Emerita at the University of California, Santa Cruz, utilizes the metaphor of the cyborg to create a framework for understanding the fluidity of identity and the increasingly blurred lines between (wo)man and machine.

One of the most relevant texts for the sex tech industry is Donna Haraway’s 1985 essay, “A Cyborg Manifesto.” Haraway, Distinguished Professor Emerita at the University of California, Santa Cruz, utilizes the metaphor of the cyborg to create a framework for understanding the fluidity of identity and the increasingly blurred lines between (wo)man and machine.

Her breakthrough perspective on the intersection of technology, sex, and identity is one of the most celebrated texts within academic feminist circles. Yet it is almost never brought up in related discussions within the tech/startup scene.

This is most likely because “A Cyborg Manifesto” is simply not part of our industry’s lexicon—but it should be!

While perhaps more approachable than many academic feminist texts, Haraway’s essay is not what one might call a “light read.” In fact, many of us simply don’t have the time to engage in philosophy.

In this edition of Sex Tech Study Guide, I’ve condensed the most relevant points of Haraway’s argument and provide examples of how her theories can be applied to improve the sex tech sector.

A realist approach to technology

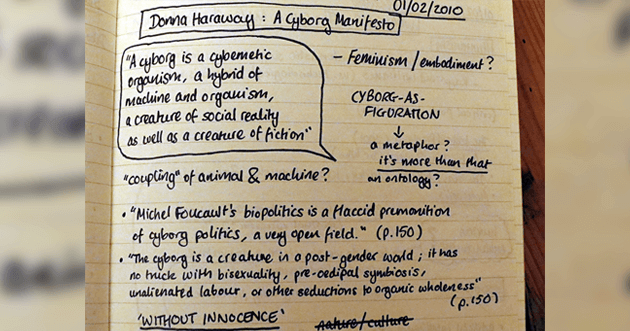

Harraway defines a cyborg as “a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction.”

Although this essay was written before the widespread use of the Internet and our almost constant connection to technological devices such as smartphones, Haraway magnificently captures our complicated relationship with machines.

She states, “We are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs.”

By accepting our role, perhaps our inclusion, in the world of machines, Haraway sets the stage for a more practical relationship with technology. She is harshly critical of techno-utopians, many of whom can be found writing for WIRED, TechCrunch, and the like.

However, she is also opposed to the tendency towards “knee-jerk technophobia.” A more useful perspective is somewhere in between.

From one perspective, a cyborg world is about the final imposition of a grid of control on the planet…From another perspective, a cyborg world might be about lived social and bodily realities in which people are not afraid of their joint kinship with animals and machines, not afraid of permanently partial identities and contradictory standpoints.

Haraway understands that technology is not neutral. Examples include the exploitation of labor (typically female) in non-western countries to make our electronics, or the lack of female test subjects in medical trials, and discrimination against female founders of tech companies looking for investments.

It is easy to see how a demonization of technology, especially by feminist activists, has occurred. However, the demonology of technology is not only impractical given our interconnected reality, it also limits our imagination.

“Taking seriously the imagery of cyborgs as other than our enemies” has some serious benefits according to Haraway. The metaphor of the cyborg and an acceptance of our singularity with technology opens up a world of possibilities.

For one, we are no longer forced to see the world in dualisms (“animal or machine” “masculine or feminine”). It provides us a framework to see ourselves as constructed, much like our machines, and therefore capable of reconstruction and software updates. Additionally, it allows us to congregate based on “affinity” and “partial identities” as opposed to essentializing and thus isolating ourselves.

Second, it gives us more control over the negative impact technology currently has. As Haraway so eloquently states, “The machine is us, our processes, an aspect of our embodiment. We can be responsible for machines; they do not dominate or threaten us.”

Taking responsibility for the social relations of science and technology means refusing an anti-science metaphysics, a demonology of technology, and so means embracing the skillful task of reconstructing the boundaries of daily life, in partial connection with others, in communication with all of our parts.

Disrupting tech’s association with masculinity

Haraway describes women’s relationship to late 20th-century technology as existing/surviving within the “Integrated Circuit.” Instead of viewing our personal, private lives as separate from technology—Haraway demonstrates how they are delicately intertwined.

She explains,“We are living through a movement from an organic, industrial society to polymorphous, information system.” As a result, women and technology are more integrated than generally thought.

Here are some of Haraway’s examples of sociotechnological transformations:

Home: “…technology of domestic work, paid homework, home-based businesses and telecommuting…” (Think: Alexa, Nest, Remote Work)

Market: “Women’s continuing consumption work, newly targeted to buy the profusion of new production from the new technologies (especially as the competitive race among industrialized and industrializing nations to avoid dangerous mass unemployment necessitates finding ever bigger new markets forever less clearly needed commodities)…advertising targeting of the numerous affluent groups and neglect of the previous mass markets” (Think: universal income deliberations, artificial intelligence, marketing in emerging markets, Facebook advertising and paid ads from social media influencers.)

Haraway’s full list is extensive as well as clairvoyant considering “A Cyborg Manifesto” was written more than 30 years ago. The key takeaways from this list are two-fold:

- Technology has an immediate impact on women’s lives, negative as well as positive.

- Women are already “in” tech, we use and create it every day.

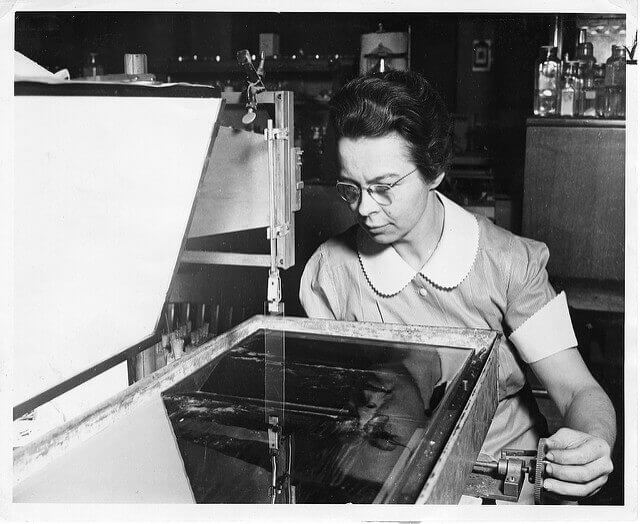

Another important point that disrupts the idea that tech is “naturally” masculine is the fact that the makers of one of the key aspects of our lives—microelectronics—are predominately Southeast Asian village women workers in Japanese and US electronics firms.

These women, Haraway writes, are “actively rewriting the texts of their bodies and societies.” She adds that at stake for these women’s navigation of a changing techno/societal landscape is survival.

Throughout Haraway’s academic works, she argues that “feminist concerns are inside of technology, not a rhetorical overlay…the issues that really matter—who lives, who dies and at what price – these political questions are embodied in technoculture. They can’t be got at in any other way.”

By reconsidering our personal lives as separate from technology and instead viewing ourselves as cyborgs—actors in an integrated circuit—women tech workers no longer need to feel like they are imposters in a boys club. Women are and have always been key actors in the development of technology.

At the same time, Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto” points to the importance of diversity in technology: technology is political, and who makes decisions in technology matters.

When women, people of color, and other underrepresented groups are included in both political and scientific discussions of technology they are better able to read what Haraway refers to as technological “webs of power” as well as form new coalitions for change.

Understanding relations between tech and sex

The above points are applicable to the technology space as a whole, but of course, unique to our industry is the matter of sex. This is where Haraway’s essay is especially useful in understanding the complicated and often overlooked entanglements of sex and technology.

The metaphor/reality of the cyborg is that they exist outside of societal narratives surrounding sex, morality, and childbirth.

“The cyborg is a creature in a post-gender world,” states Haraway, where “replication is uncoupled from organic reproduction.” In this way, the cyborg provides an example of how technology—rather than being the enemy of societal progress—can, in fact, help us to imagine the possibility of sex removed from human, cultural stigmas and categorizations.

Feminist theorists argue that gender is a societal construct. That is, our gender identity is constructed as we mature, primarily by societal norms and pressures. In a sense, our genetic identification (ourselves without society) is the biological form that is then constructed upon. All of us are a combination of biological and artificial. Again, we are cyborgs. This view prompts us to view sexuality in each of us as a biological and societal cyborg.

Late twentieth-century machines have made thoroughly ambiguous the difference between natural and artificial, mind and body, self-developing and externally designed, and many other distinctions that used to apply to organisms and machines. Our machines are disturbingly lively, and we ourselves frighteningly inert.

Haraway argues that In the age of technology “ideologies of sexual reproduction can no longer reasonably call on notions of sex and sex role as organic aspects in natural objects like organisms and families.” By viewing sex as both externally designed and organic, discussions of sex become less morally weighted.

Haraway’s analysis is incredibly important for the sex tech industry, as it provides us a way of explaining sexuality as not just a part of human nature, but also very much a part of technological reality.

Sex robots, genetic engineering, birth control, online streaming adult entertainment—these are not separate from biological human sexuality, in today’s world they are one in the same—hence the usefulness of the “cyborg” comparison.

Most importantly, “A Cyborg Manifesto” cleverly argues for the entanglement of technology and politics. Everything we do in our lives today is somehow related to technology, not excluding and maybe especially sex. Haraway’s essay provides a necessary framework for thinking about sex tech progressively—the moralities, challenges, and opportunities unique to this sector.

Annie Brown is the founder of Lips— a socially responsible social media platform that provides a safe space on the Internet for women* to express their experiences openly and honestly. She has presented at The Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality (SSSS) and is a guest lecturer at UC San Diego’s Rady School of Management.

Image sources: Justin Pickard, Wikimedia Commons, Smithsonian Institution

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.